Roles of adipocytes and adipose-derived stem cells in the lipophilic metastasis of ovarian cancer

-

摘要: 卵巢癌在妇科恶性肿瘤中死亡率最高,晚期卵巢癌患者5年生存率不足30%,转移可能是导致其高致死率的首要原因。卵巢癌最主要的转移部位是网膜,而网膜上丰富的脂肪组织提示其可能存在"嗜脂性"转移的特征。脂肪细胞及脂肪来源的干细胞(adipose-derived stem cells,ADSC)是网膜组织最重要的组成部分,能够通过分泌多种细胞因子和脂肪因子、改变卵巢癌细胞的糖脂代谢方式等诱导卵巢癌细胞向网膜迁移,并通过血管内皮细胞、肿瘤相关巨噬细胞及癌相关成纤维细胞的相互作用,参与适宜卵巢癌细胞转移与定植的微环境。为预防与阻断卵巢癌转移,提高卵巢癌患者的生存率,本文将就脂肪细胞与ADSC在卵巢癌"嗜脂性"转移中的作用研究进展进行综述。Abstract: Ovarian cancer is the most common cause of cancer-associated deaths among the gynecological malignancies. The 5-year survival rate of the patients is less than 30%. This high mortality rate is mainly due to the metastasis. Adipose-rich omentum is the main site of metastasis, suggesting that ovarian cancer may have the characteristic of "lipophilic" metastasis. Adipocytes and adiposederived stem cells are the most important components of the omentum. These cell ssecrete cytokines and adipokines and modify glucose and lipid metabolism to induce migration of ovarian cancer cells to the omentum. Simultaneously, they create a suitable microenvironment for the metastasis and colonization of these cancer cells by interacting with vascular endothelial cells, tumor-associated macrophages, and cancer-associated fibroblasts. This article reviews the recent advances in the role of adipocytes and adipose-derived stem cells in the "lipophilic" metastasis of ovarian cancer, aiming at providing new ideas for preventing ovarian cancer metastases and improving the survival rate of patients with ovarian cancer.

-

Keywords:

- adipocytes /

- adipose-derived stem cells (ADSC) /

- ovarian neoplasms

-

卵巢癌是妇科三大恶性肿瘤之一,虽发病率仅占女性恶性肿瘤的2.5%,但死亡率却位于妇科恶性肿瘤之首[1]。卵巢癌早期无明显临床症状,明确诊断时大多已合并转移。晚期卵巢癌患者的5年相对生存率仅为29%,但未合并转移的患者可达到92%[2],因此转移可能是导致高致死率的首要原因。“种子和土壤”假说认为肿瘤的转移依赖于癌细胞(种子)和特定器官微环境之间的相互作用(土壤)[3]。卵巢癌以种植转移为主,其中网膜转移最为多见。Pradeep等[4]通过对小鼠异种共生模型研究证实,卵巢癌可经血行转移至网膜,提示网膜微环境与卵巢癌定向转移之间的关系。为预防与阻断卵巢癌转移,提高卵巢癌患者的生存率,本文将就脂肪细胞与脂肪来源的干细胞(adipose-derived stem cells,ADSC)在卵巢癌“嗜脂性”转移中的作用研究进展进行综述。

1. 卵巢癌转移的“嗜脂性”

研究显示,约有80%的高级别浆液性卵巢癌患者存在网膜转移[4-5],卵巢癌细胞对富含脂肪的网膜组织的特殊“嗜好”体现出其“嗜脂性”转移的特征。网膜是内脏脂肪的重要储存库,内脏脂肪组织代谢活跃可分泌脂肪因子和促炎细胞因子,促进如肝癌、肠癌、前列腺癌等多种恶性肿瘤的发生与发展[6]。网膜上的脂肪细胞及ADSC,简称脂肪干细胞,在卵巢癌“嗜脂性”转移的过程中发挥重要作用。

2. 脂肪细胞及ADSC与卵巢癌细胞的相互作用

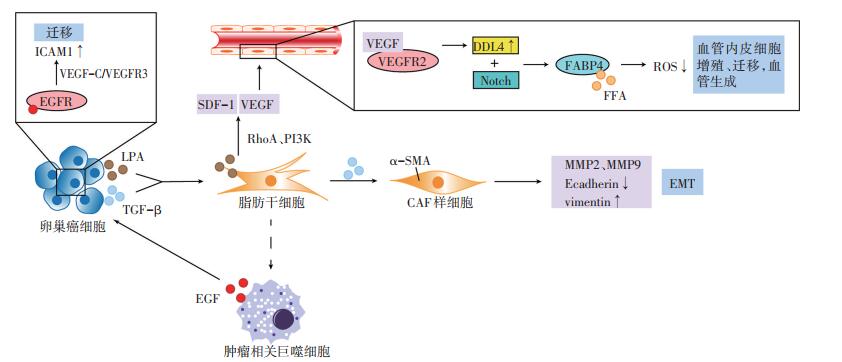

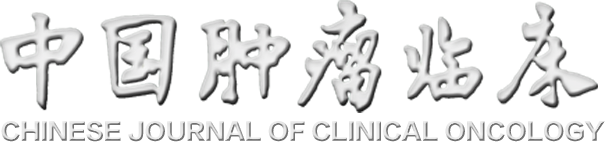

脂肪细胞及ADSC能通过分泌细胞因子和脂肪因子、改变卵巢癌细胞的糖、脂代谢方式,诱导卵巢癌的“嗜脂性”转移(图 1)[5, 7-15]。

2.1 分泌细胞因子诱导“嗜脂性”转移

脂肪细胞与ADSC分泌的细胞因子能诱导卵巢癌的“嗜脂性”转移。脂肪细胞通过分泌白介素-8(interleukin-8,IL-8)、单核细胞趋化蛋白-1(monocyte chemotactic protein-1,MCP-1)诱导卵巢癌细胞向网膜迁移,可能与其所形成的趋化因子的浓度梯度有关[5]。另外,MCP-1能与卵巢癌细胞表面的趋化因子受体2(chemokine receptor 2,CCR2)结合,激活PI3K/AKT/ mTOR信号通路,促使卵巢癌细胞向网膜转移。使用二甲双胍抑制网膜脂肪细胞分泌MCP-1后,卵巢癌的网膜转移灶减少[7]。ADSC分泌的白介素-6(interleukin- 6,IL-6),也能结合卵巢癌细胞表面的白介素-6受体(interleukin-6 receptor,IL-6R),激活JAK/STAT信号途径,诱导上皮间质转化,利于卵巢癌的转移[8]。

2.2 分泌脂肪因子促使卵巢癌转移

脂肪组织分泌的脂肪因子瘦素,能与卵巢癌细胞表面的瘦素受体(OB-Rb)结合,激活ERK1/2、JNK1/2通路,诱导金属基质蛋白酶7(matrix metalloproteinase 7,MMP7)表达[9];上调RhoA蛋白,激活RhoA/ROCK途径,诱导肌球蛋白磷酸酶肌球蛋白结合亚基1(myosin phosphatase targeting subunit 1,MYPT1)及尿激酶(urokinase,uPA)的活化[10]。MMP7及uPA所激活的纤溶酶原能降解细胞外基质[9],MYPT1则能重组细胞骨架,刺激应力纤维及局部黏附复合体的形成,调节细胞运动[11]。MMP7、uPA和MYPT1协同促进卵巢癌的迁移与侵袭。与瘦素相反,脂联素能减少卵巢癌细胞的增殖[16],但目前尚未发现其对卵巢癌网膜转移的抑制作用。

2.3 改变卵巢癌细胞的代谢方式

脂肪细胞及ADSC能够改变卵巢癌细胞的糖、脂代谢方式,促进卵巢癌的“嗜脂性”转移。Salimian等[12]研究发现,ADSC来源的精氨酸能诱导卵巢癌细胞中一氧化氮(nitrogen,NO)的合成,使得NO浓度升高,线粒体有氧呼吸被抑制,使葡萄糖经无氧酵解及磷酸戊糖途径代谢。一方面,即使在有氧条件下癌细胞也更倾向于通过糖酵解获取能量;另一方面,磷酸戊糖途径产生的还原型烟酰胺腺嘌呤二核苷酸磷酸(nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate,NADPH)能有效地减少活性氧(reactive oxygen species,ROS)的产生,从而有利于癌细胞的存活。

将网膜脂肪细胞与卵巢癌细胞共培养后,脂肪细胞释放的游离脂肪酸(free fatty acid,FFA)增多,同时诱导癌细胞表面脂肪酸结合蛋白4(fatty acid-binding protein4,FABP4)及CD36的表达,促使FFA由脂肪细胞向卵巢癌细胞转移,增加卵巢癌细胞的迁移与侵袭力。脂肪酸分解产生的腺苷三磷酸(adenosine triphosphate,ATP)较葡萄糖的有氧分解少,ATP减少促使卵巢癌细胞中的AMP依赖的蛋白激酶(adenosine 5'-monophosphate AMP-activated protein kinase,AMPK)磷酸化,使其下游的乙酰辅酶A羧化酶(acetyl-CoA carboxylase,ACC)磷酸化失活,激活肉毒碱棕榈酰基转移酶1(carnitine palmitoyltransferase,CPT1),介导乙酰辅酶A不断地由细胞质向线粒体转移,进一步启动脂肪酸β氧化[5, 13-14]。此外,脂肪细胞还能诱导盐诱导激酶2(saltinducible kinase 2,SIK2)的钙依赖性激活,促使ACC失活[15]。ACC失活与CPT1活化抑制内源性脂质的合成和葡萄糖氧化,使癌细胞通过糖酵解及摄取外源性脂质后,以β氧化形式来供能,能量的不足又促使其加速脂肪酸的摄取,由此形成一个恶性循环,诱使其向富含脂肪细胞的网膜转移,表现出“嗜脂性”的特点[5, 13-14]。John等[17]发现富含半胱氨酸的酸性分泌蛋白(secreted protein acidic and rich in cysteine,SPARC)能抑制脂肪细胞释放FFA,同时下调卵巢癌细胞表面FABP4与CD36的表达,减少其对脂肪酸的摄取作用而抑制网膜转移。

3. ADSC与非卵巢癌细胞的相互作用

ADSC通过与血管内皮细胞、肿瘤相关巨噬细胞(tumor-associated macrophage,TAM)及癌相关成纤维细胞(cancer-associated fibroblasts,CAF)的相互作用参与网膜微环境(图 2)[18-21]。

3.1 血管内皮细胞

ADSC与血管内皮细胞的相互作用促进新生血管形成,为卵巢癌细胞提供增殖所需的营养和血行转移的途径,在“嗜脂性”转移中至关重要[4]。Jeon等[18]研究发现,使用卵巢癌细胞和ADSC共培养上清处理人脐静脉内皮细胞,其形成小管的速度及密度明显增加。癌细胞来源的溶血磷脂酸(lysophosphatidic acid,LPA)能通过激活ADSC中的RhoA及PI3K途径诱导其分泌基质细胞衍生因子-1α(stromal cell-derived factor-1α,SDF- 1α)和血管内皮生长因子(vascular endothelial growth factor,VEGF)。VEGF能诱导血管内皮细胞的增殖与迁移,是血管生成过程中必不可少的生长因子,其与血管内皮生长因子受体2(vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2,VEGFR2)结合后,诱导内皮细胞表面DLL4(delta like canonical notch ligand 4)表达增加,DLL4能结合相邻细胞表面的Notch受体,激活Notch通路,调节FABP4的转录。FABP4结合内皮细胞中的FFA,保护其不受FFA诱导产生的ROS影响。此外,远离卵巢癌脂肪组织的血管内皮细胞中的FABP4表达量,显著高于邻近的癌组织[19],表明其可能主要在卵巢癌转移微环境的建立与维持中起重要作用。

3.2 TAM

ADSC具有抗炎及促进免疫耐受的功能。在炎症性疾病模型中,ADSC所诱导的M1型巨噬细胞向M2型的转换能够缓解炎症反应[22]。但在肿瘤相关性疾病中,M2型巨噬细胞常被称为TAM,能抑制抗肿瘤免疫应答,与免疫抑制的肿瘤微环境密切相关。TAM分泌的表皮生长因子(epidermal growth factor,EGF),与卵巢癌细胞表面的表皮生长因子受体(epidermal growth factor receptor,EGFR)结合,上调VEGF-C/VFGFR3信号,诱导肿瘤微环境中细胞间黏附分子-1(integrin/intercellular adhesion molecule-1,ICAM-1)的表达,从而促使卵巢癌细胞的迁移[20]。但微环境中TAM的来源尚未明确,ADSC诱导极化的TAM可能是其重要来源之一。

3.3 CAF

卵巢癌细胞能通过转化生长因子-β1(transforminggrowth factor-β1,TGF-β1)途径,诱导ADSC向CAF分化,表达α-平滑肌肌动蛋白(α-smooth muscle actin,α-SMA)并发挥与CAF相似的功能,如表达MMP2与MMP9降解细胞外基质,下调E-cadherin,上调波形蛋白(vimentin),诱导上皮间质转化,利于癌细胞转移[21]。

4. 非脂肪细胞及ADSC与卵巢癌的转移

网膜组织中亦存在多种免疫细胞和基质细胞,如中性粒细胞能在卵巢癌细胞分泌的IL-8、MCP-1的作用下,迁移至网膜并形成中性粒细胞胞外陷阱(neutrophil extracellular traps,NETs),直接捕获循环卵巢癌细胞并使其定植于网膜[23]。卵巢癌细胞来源的TGF-β能促使CAF分泌IL- 6、趋化因子(chemokine,CXCL)10和CXCL5,这些细胞因子以糖原磷酸化酶依赖性的方式诱导卵巢癌细胞中的糖原动员,促使其增殖与迁移[24]。

5. 结语

综上所述,网膜脂肪细胞、ADSC、基质细胞和免疫细胞共同参与适宜卵巢癌转移与定植的网膜微环境,并通过趋化作用、直接捕获、代谢重编程等多种途径诱导卵巢癌细胞向网膜转移。而对于网膜微环境中脂肪细胞及ADSC的干预或许能够有效地阻断或抑制卵巢癌细胞的“嗜脂性”转移,为卵巢癌的治疗带来新的希望。

-

[1] Torre LA, Trabert B, Desantis CE, et al. Ovarian cancer statistics, 2018[J]. CA Cancer J Clin, 2018, 68(4):284-296. DOI: 10.3322/caac.21456

[2] Lheureux S, Gourley C, Vergote I, et al. Epithelial ovarian cancer[J]. Lancet, 2019, 393(10177):1240-1253. DOI: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32552-2

[3] Peinado H, Zhang H, Matei IR, et al. Pre-metastatic niches:organspecific homes for metastases[J]. Nat Rev Cancer, 2017, 17(5):302-317. DOI: 10.1038/nrc.2017.6

[4] Pradeep S, Kim SW, Wu SY, et al. Hematogenous metastasis of ovarian cancer:rethinking mode of spread[J]. Cancer Cell, 2014, 26(1):77-91. DOI: 10.1016/j.ccr.2014.05.002

[5] Nieman KM, Kenny HA, Penicka CV, et al. Adipocytes promote ovarian cancer metastasis and provide energy for rapid tumor growth[J]. Nat Med, 2011, 17(11):1498-1503. DOI: 10.1038/nm.2492

[6] Montano-Loza AJ, Mazurak VC, Ebadi M, et al. Visceral adiposity increases risk for hepatocellular carcinoma in male patients with cirrhosis and recurrence after liver transplant[J]. Hepatology, 2018, 67(3):914-923. DOI: 10.1002/hep.29578

[7] Sun C, Li X, Guo E, et al. MCP-1/CCR-2 axis in adipocytes and cancer cell respectively facilitates ovarian cancer peritoneal metastasis[J]. Oncogene, 2020, 39(8):1681-1695. DOI: 10.1038/s41388-019-1090-1

[8] Kim B, Kim HS, Kim S, et al. Adipose stromal cells from visceral and subcutaneous fat facilitate migration of ovarian cancer cells via IL-6/JAK2/STAT3 pathway[J]. Cancer Res Treat, 2017, 49(2):338-349. DOI: 10.4143/crt.2016.175

[9] Ghasemi A, Hashemy SI, Aghaei M, et al. Leptin induces matrix metalloproteinase 7 expression to promote ovarian cancer cell invasion by activating ERK and JNK pathways[J]. J Cell Biochem, 2018, 119(2):2333-2344. DOI: 10.1002/jcb.26396

[10] Ghasemi A, Hashemy SI, Aghaei M, et al. RhoA/ROCK pathway mediates leptin-induced uPA expression to promote cell invasion in ovarian cancer cells[J]. Cell Signal, 2017, 32:104-114. DOI: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2017.01.020

[11] Kato S, Abarzua-Catalan L, Trigo C, et al. Leptin stimulates migration and invasion and maintains cancer stem-like properties in ovarian cancer cells:an explanation for poor outcomes in obese women[J]. Oncotarget, 2015, 6(25):21100-21119. DOI: 10.18632/oncotarget.4228

[12] Salimian Rizi B, Caneba C, Nowicka A, et al. Nitric oxide mediates metabolic coupling of omentum-derived adipose stroma to ovarian and endometrial cancer cells[J]. Cancer Res, 2015, 75(2):456-471. DOI: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-14-1337

[13] Ladanyi A, Mukherjee A, Kenny HA, et al. Adipocyte-induced CD36 expression drives ovarian cancer progression and metastasis[J]. Oncogene, 2018, 37(17):2285-2301. DOI: 10.1038/s41388-017-0093-z

[14] Mukherjee A, Chiang CY, Daifotis HA, et al. Adipocyte-induced FABP4 expression in ovarian cancer cells promotes metastasis and mediates carboplatin resistance[J]. Cancer Res, 2020, 80(8):1748-1761. DOI: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-19-1999

[15] Miranda F, Mannion D, Liu S, et al. Salt-inducible kinase 2 couples ovarian cancer cell metabolism with survival at the adipocyte-rich metastatic niche[J]. Cancer Cell, 2016, 30(2):273-289. http://www.wanfangdata.com.cn/details/detail.do?_type=perio&id=cb16393dd823130df4b49968e88c76a4

[16] Hoffmann M, Gogola J, Ptak A. Adiponectin reverses the proliferative effects of estradiol and IGF-1 in human epithelial ovarian cancer cells by downregulating the expression of their receptors[J]. Horm Cancer, 2018, 9(3):166-174. DOI: 10.1007/s12672-018-0331-z

[17] John B, Naczki C, Patel C, et al. Regulation of the bi-directional crosstalk between ovarian cancer cells and adipocytes by SPARC[J]. Oncogene, 2019, 38(22):4366-4383. DOI: 10.1038/s41388-019-0728-3

[18] Jeon ES, Heo SC, Lee IH, et al. Ovarian cancer-derived lysophosphatidic acid stimulates secretion of VEGF and stromal cell-derived factor-1 alpha from human mesenchymal stem cells[J]. Exp Mol Med, 2010, 42(4):280-293. DOI: 10.3858/emm.2010.42.4.027

[19] Harjes U, Bridges E, Gharpure KM, et al. Antiangiogenic and tumour inhibitory effects of downregulating tumour endothelial FABP4[J]. Oncogene, 2017, 36(7):912-921. DOI: 10.1038/onc.2016.256

[20] Yin M, Li X, Tan S, et al. Tumor-associated macrophages drive spheroid formation during early transcoelomic metastasis of ovarian cancer[J]. J Clini Invest, 2016, 126(11):4157-4173. DOI: 10.1172/JCI87252

[21] Tang H, Chu Y, Huang Z, et al. The metastatic phenotype shift toward myofibroblast of adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells promotes ovarian cancer progression[J]. Carcinogenesis, 2020, 41(2):182-193. DOI: 10.1093/carcin/bgz083

[22] Park HJ, Kim J, Saima FT, et al. Adipose-derived stem cells ameliorate colitis by suppression of inflammasome formation and regulation of M1-macrophage population through prostaglandin E2[J]. Biochem Biophys Res Commun, 2018, 498(4):988-995. DOI: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2018.03.096

[23] Lee W, Ko SY, Mohamed MS, et al. Neutrophils facilitate ovarian cancer premetastatic niche formation in the omentum[J]. J Exp Med, 2019, 216(1):176-194. DOI: 10.1084/jem.20181170

[24] Curtis M, Kenny HA, Ashcroft B, et al. Fibroblasts mobilize tumor cell glycogen to promote proliferation and metastasis[J]. Cell Metab, 2019, 29(1):141-155. DOI: 10.1016/j.cmet.2018.08.007

-

期刊类型引用(5)

1. 单尧飞,玛依努尔·买买提明,胡佳俊. 超声造影参数与早期卵巢癌患者腹腔镜术后淋巴结转移的相关性研究. 中外医学研究. 2024(21): 66-70 .  百度学术

百度学术

2. 金影. 脂代谢异常与卵巢癌的相关性研究进展. 中华全科医师杂志. 2024(11): 1220-1225 .  百度学术

百度学术

3. 周莹,平全红,姜振环. 妇科恶性肿瘤与2型糖尿病关系的研究进展. 癌症进展. 2023(17): 1865-1867+1909 .  百度学术

百度学术

4. 王卉,陈学平,陈运,曹颖诗,陈瑶,刘国炳,黄莉萍. ENTPD5在上皮性卵巢癌组织中高表达:基于Oncomine数据库及生物信息学方法. 南方医科大学学报. 2021(04): 555-561 .  百度学术

百度学术

5. 窦金利,李昉璇,李世霞,刘俊田. 代谢综合征与上皮卵巢癌发病风险及临床病理特征的相关性研究. 中国肿瘤临床. 2020(19): 973-976 .  本站查看

本站查看

其他类型引用(2)

下载:

下载: