Advances in chronic liver diseases with abnormal chemokine expression and colorectal cancer liver metastasis

-

摘要: 近年来,中国结直肠癌(colorectal cancer,CRC)发病率快速上升,已成世界第一结直肠癌大国。肝脏局部微环境通过趋化因子-受体轴,募集特定亚群髓系细胞,促进结直肠癌肝转移(colorectal liver metastasis,CRLM)病灶进展。中国大部分CRC患者同时伴发慢性乙型肝炎(chronic hepatitis B,CHB)、非酒精性脂肪性肝病(nonalcoholic fatty liver disease,NAFLD)、酒精性肝病(al-coholic liver disease,ALD)等非肿瘤性慢性肝脏疾病,上述慢性肝病中也伴随有趋化因子表达的异常改变,其中有部分已被发现与肿瘤转移相关。本文对CRC、CHB、NAFLD及ALD近年来在中国的流行病学变化趋势进行简要回顾,对上述不同类型慢性肝病中所伴发的趋化因子的异常改变进行简要总结。对照已报道与CRLM相关的趋化因子种类及其机制,对不同慢性肝病可能通过类似的趋化因子-髓系细胞途径促进CRLM的发生及其机制进行综述。Abstract: The incidence of colorectal cancer (CRC) is increasing rapidly in China. In fact, in 2019, China was the country with the highest CRC case numbers in the world. Specific myeloid cell subsets are recruited into the liver micro-environment via chemokine-receptor axis and facilitate the progression of colorectal liver metastasis(CRLM). In China, many CRC patients suffer concomitant chronic liver diseases, such as chronic hepatitis B (CHB), nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), and alcoholic liver disease (ALD). Aberrant expression of chemokines is observed in these chronic liver diseases, and some of them have been associated with cancer metastasis. Here, first, we review the recent epidemiological trends of CRC, CHB, NAFLD, and ALD in China, briefly summarizing the abnormal chemokine changes in these chronic liver diseases. Furthermore, we review the potential mechanisms that may explain how different chronic liver diseases facilitate CRLM, focusing on the chemokine-myeloid cell subsets axis, which has been previously reported to be related to CRLM.

-

1. CRC及CRLM的流行病学现状

结直肠癌(colorectal cancer,CRC)在世界范围内仍维持高发,至2018年,全球CRC新发病例数(1 800 977例)及死亡病例数(861 663例)均较前持续上升;其整体发病率位居恶性肿瘤第3位,而死亡率则高居第2位[1]。

中国CRC发病率曾长期维持在较低水平,但近年来快速上升。1973年至1975年,其粗死亡率仅为4.60/ 10万;2004年至2005年,已经达到7.25/10万,提高了57.6%。城市居民更为突出,上海市2003年至2007年CRC粗死亡率高达2.42/10万,已是1973年至1975年城市居民CRC死亡率的近400%[2]。2020年,预期中国整体CRC年龄标化(age standardized rate,ASR)发病率和死亡率将分别达到20.7/10万和8.6/10万,较2003年分别上升61.7%和45.8%[3]。2015年度统计显示,全国范围内CRC新发病例数在男性和女性分别居恶性肿瘤第5和第4位,死亡病例数均居第5位[4]。2018年度统计显示,虽然CRC死亡病例数仍居恶性肿瘤第5位,其新发病例数在男性和女性均已上升至第3位;2018年中国新发病例为521 490例,占全球新发病例数的28.2%,远超第2位的美国(155 098例)[5]。CRC已成为严重危害中国人民健康的恶性肿瘤之一。

CRC是转移性肝癌最常见的原发瘤来源。远处转移是CRC患者5年生存率最主要的独立预后因素,其中肝脏又是CRC最常转移至的器官,且通常是唯一累及的转移器官。14%~25%的CRC患者发生同时性肝转移(synchronous colorectal liver metastases,synCRLM),另外有20%~33%的患者在随后治疗中出现异时性肝转移(metachronous liver metastases,metCRLM)[6-7],最终超过一半的CRC患者直接死于肝转移。因此,CRLM是影响CRC治疗效果及预后的关键因素。

2. 趋化因子-髓系细胞在CRLM中的重要作用

不同的趋化因子通过其受体,特异性趋化募集某些亚群的髓系细胞(myeloid cells)并促进肿瘤进展[8]。这一机制在肿瘤转移中也具有重要作用。

2.1 CCL2

CCL2又称单核细胞趋化蛋白1(monocyte che moattractant protein-1,MCP-1)。本课题组报道CCL2在促进CRLM进展中具有重要作用:CRC细胞可主动产生CCL2,通过其受体CCR2,从骨髓募集CD11b+/Gr-1mid/ CCR2+表型的单核/巨噬细胞浸润致肝内CRLM病灶,继而通过促血管生成机制,促进转移灶进展[9]。此研究结论已被后续更多研究进一步证实。

2.2 CCL20

CCL20又称肝活化调节趋化因子(liver activation regulated chemokine,LARC)或巨噬细胞炎性蛋白3α(macrophage inflammatory protein-3 alpha,Mip-3α),其唯一受体为CCR6。CCL20通过CCR6主要趋化T淋巴细胞、部分类型的B淋巴细胞及树突状细胞(dendritic cell,DC)[10]。

CRC中CCR6水平显著高于正常结直肠黏膜上皮[11-12]。CRC原发瘤中CCR6表达水平是synCRLM的独立危险因素[11]。

血清CCL20水平在各个临床分期的CRC中均是独立的预后因素,同时是独立的肝转移预测因素[13]。已发生肝转移的CRC患者原发瘤中CCL20表达的阳性率显著高于无肝转移者,与总生存期、无病生存期均显著相关[14]。

2.3 CXCL9/10/11

CXCL9又称γ-干扰素诱导的单因子(monokine induced by gamma interferon,MIG),CXCL10又称γ-干扰素诱导蛋白10(interferon gamma-induced protein 10,IP-10),CXCL11称干扰素诱导T细胞趋化物α(interferon-inducible T- cell alpha chemoattractant,iTAC)或γ-干扰素诱导蛋白9(interferon gamma-in ducible protein 9,IP-9)。CXCL9/10/11均通过CXCR3发挥功能。

有研究根据Gene Expression Omnibus数据库中490余例CRC患者的资料分析显示,CXCL9/10/11三个趋化因子的水平均与CRC患者无病生存期显著相关,CXCL10/ 11则均与CRC患者总生存期显著相关[15]。

CRLM中,两个特殊的髓系细胞亚群(CD68+和CD11b+)分别通过产生CXCL9/10,趋化T细胞至肝转移灶的浸润前缘,这些T细胞继而产生CCL5,通过其受体CCR5直接作用于CRC细胞,或作用于肿瘤相关巨噬细胞(tumor-associated macrophages,TAMs),发挥促肿瘤效应[16]。

CRC患者外周血CXCL10水平显著高于健康志愿者,血清CXCL10水平随CRC肿瘤UICC分期的升高(Ⅰ~Ⅳ期)及原发瘤T分期的升高(T1~T4)显著逐步升高,而血清CXCL10水平被证实是肝转移的独立预测因素[17]。

3. 中国CRC患者同时伴发的各种非肿瘤性慢性肝脏疾病

3.1 慢性乙型病毒性肝炎(chronic hepatitis B,CHB)

2016年全球乙肝表面抗原(hepatitis B surface an tigen,HBsAg)阳性率据估算为3.9%,中国为6.1%,虽已不再居世界首位,但庞大的人口基数使乙肝人群数仍为世界最高[18]。因此,中国有相当比例的CRC患者同时伴发CHB。本课题组的一项研究显示,在山东地区CRC患者中,伴发乙肝者占6.05%[19],这一比例与中国6.1%的HBsAg阳性率非常吻合。以此阳性率计算,2018年中国新发的521 490例CRC例中,有约31 811例同时伴有CHB,这一数字是美国每年新发肝癌病例数的两倍(15 876例)。

3.2 非酒精性脂肪性肝病(nonalcoholic fatty liver disease,NAFLD)

目前中国NAFLD患者数量已居世界首位,患病率高达29.2%[20]。研究预测至2030年,NAFLD高发国家中患病率增速最快的仍将是中国,病例数预计增加29.1%,达3.15亿例[21]。

按29%的患病率估算,2018年中国有151 232例新发CRC患者同时伴有NAFLD,已非常接近排名第2位的美国全国新发CRC病例数。实际病例数可能将超过此数,因为在CRC高发的50~69岁人群中,NAFLD患病率更高[20]。

3.3 酒精性肝病(alcoholic liver disease,ALD)

过去三十年间,中国年人均酒精摄入量大幅增加,超过绝大多数其他国家[22]。1999年,中国肝硬化病例中10.8%为酗酒所致,至2003年这一比例已上升至24%[23]。

因缺乏权威的全国ALD患病率资料,如仅以8%左右的患病率估算[24],中国每年新发CRC患者中,有超过4万例伴有ALD。

4. 各种慢性肝病伴随趋化因子异常表达

4.1 CHB

趋化因子表达在CHB中有显著变化。国内一项研究对健康对照者、无症状乙肝携带者及慢性活动性乙肝患者中血清趋化因子表达谱进行系统性比较[25],发现乙肝患者血清趋化因子显著升高的为CCL20、CXCL6与CXCL9/10/11,而且这几个趋化因子的表达水平从健康者到无症状乙肝携带者,再到活动性乙肝患者,依次显著升高。

有其他研究证实CXCL10水平在CHB患者中升高,且与血清谷丙转氨酶(alanine aminotransferase,ALT)及乙肝病毒脱氧核糖核酸(HBV-DNA)水平显著相关[26]。乙肝病毒X蛋白(hepatitis B virus X protein,HBx)可通过TRAF2/TAK1信号通路激活NF-κB,后者上调CXCL10表达后,趋化外周血淋巴细胞浸润入肝脏[27]。

4.2 NAFLD

与健康对照者相比,NAFLD患者血清CCL2、CCL19水平显著升高。分层研究显示,CCL2水平在非酒精性脂肪性肝炎(nonalcoholic steatohepatitis,NASH)患者中显著高于单纯脂肪肝,提示CCL2水平升高可能在单纯脂肪肝到NASH的进展过程中具有重要意义[28]。

与正常肝组织相比,NAFLD肝纤维化组织中CCL20 RNA水平显著上升,而患者血清中CCL20蛋白水平也显著升高;CCL20在NAFLD中趋化幼稚树突状细胞,而后者产生多种炎性分子,介导肝纤维化的发生[29]。CCL20受miR-590-5p调控,其水平随NAFLD进展及肝脏星状细胞激活的不同阶段逐步升高,并在后者中引起细胞外基质相关成分表达的增加,进而引起纤维化[30]。

NASH患者外周血及肝脏内CXCL10水平显著升高,且与上述CCL2水平正相关。外周血CXCL10水平与肝小叶炎症程度相关,是NAFLD患者进展至NASH的独立危险因素[31]。

4.3 ALD

血清CCL2水平在酒精性肝炎(alcoholic hepati tis,AH)患者中高于健康者,且与血清天门冬氨酸氨基转移酶(aspartate aminotransferase,AST)及肌酐(creatinine,Cr)水平相关,而在无活动性炎症的酒精性肝硬变患者中则无显著升高[32]。

ALD患者血浆CCL2水平显著高于健康者,其中AH患者血浆及肝内CCL2水平显著高于无AH者,血浆及肝内CCL2水平均与疾病严重程度相关,肝内CCL2水平与中性粒细胞浸润及IL-8表达相关,提示CCL2升高募集中性粒细胞浸润,在ALD发病机制中具有重要作用[33]。

综上所述,上述几类慢性肝病中,均伴随有与CRLM密切相关的趋化因子的异常表达。

5. 伴发不同慢性肝病对CRLM风险影响的研究现状

多数早期研究认为,伴发慢性肝病降低CRLM发生率。这些研究通常为较小样本的回顾性研究,且未区分具体肝病类型,也未充分考虑不同治疗方式之间,或同一治疗方式的规范性对肝转移的影响。新近一些研究开始提出不同结论,认为CRC伴发慢性肝病会增加发生肝转移的几率。

5.1 伴发CHB对CRLM风险的影响

早期研究认为伴发CHB者CRLM发病率降低。国内Qiu等[34]报道伴发CHB或CHC者CRLM发病率为14.2%,而对照组则为28.2%。这些研究均为回顾性,也未区分synCRLM与metCRLM。

虽然CRC与胰腺癌均同样通过门静脉系统转移至肝脏,有报道伴发CHB反而显著增加胰腺癌患者肝转移的发病率[35]。本研究认为原因可能在于胰腺癌预后极差,远逊于CRC,即使能获得根治性切除,术后也缺乏真正有效的辅助治疗方案,这就使得不同治疗方式所致的偏倚小于CRC,伴发CHB本身对肝转移的影响得以充分显现。

本课题组通过一项临床大样本的回顾性横断面研究对此问题进行了研究。研究对象为连续6年4033例入院治疗的初诊CRC患者。研究针对synCRLM患病率在伴发与不伴发CHB的患者间的差异。所有患者均为初诊CRC,之前未接受任何治疗,由于不考虑治疗后出现的metCRLM避免了前述不同治疗方式对肝转移的影响。研究最终证实,伴发CHB显著增加CRC患者发生肝转移的风险[19]。

5.2 伴发NAFLD对CRLM风险的影响

通过高脂饮食诱导C57Bl/6小鼠产生肥胖与非酒精性脂肪肝后接种MC38肿瘤细胞,可观察到非酒精性脂肪肝小鼠较对照组肝转移灶形成显著增多,且与MC38细胞的TLR4(Toll-like receptor 4)有关[36]。在NAFLD状态下,NLRC4(NOD-like receptor C4)引起TAMs的M2极化并产生IL-1β、VEGF,促进CRLM的生长[37]。

一项对2 715例CRLM患者的前瞻性临床研究结果则显示,在根治性CRLM切除后,脂肪肝(fatty liver disease,FLD)是肝脏局部复发的独立危险因素[38]。也有观点认为,对此结果需要谨慎解读:一方面,因为切除的是肝转移灶,FLD有可能增加手术困难及术后并发症的几率,进而影响术后肿瘤复发,即FLD对肿瘤复发的影响并非源于其自身;另一方面,较晚期的患者需要更长、更强的化疗,导致肝脏的脂肪变性,即FLD间接代表了更晚的分期,从而也间接与预后相关。

总体来说,伴发NAFLD可促进CRC的发生与进展。近年来已开始关注NAFLD对CRLM的具体影响,但尚无一致广泛接受的结论,需进一步深入研究。

5.3 伴发ALD对CRLM风险的影响

酒精喂食诱导Rag-1缺陷小鼠形成ALD后,脾内注射LS174T人CRC细胞,可观察到与对照组相比,ALD组形成肝转移病灶更早、更严重[39]。MC38小鼠CRC细胞株在同一动物模型进行的实验也显示,接种肿瘤细胞前、后或全程喂食酒精均可显著增加肝转移病灶,并增加肝内滞留的MC38肿瘤细胞数目[40]。

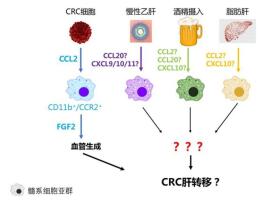

一项对133例CRC患者的研究报道,酒精摄入和肿瘤侵犯血管是肝转移的独立危险因素[41]。此外未见更多关于ALD影响CRLM的研究报道。各种慢性肝病通过趋化因子-髓系细胞轴促进CRLM的形成与进展示意见图 1。

6. 结语

综上所述,多种慢性肝病可致特定趋化因子表达上调,同时这些趋化因子又与CRLM相关。结合这两点,伴发慢性肝病是否可以通过改变趋化因子表达,募集特定亚群髓系细胞至肝脏微环境,最终增加CRC患者发生肝转移的风险值得进一步研究证实。未来有望在不同病理因素所致CRLM中找到共性,发现潜在的共同干预靶点,从而整体改善患者预后。但目前尚未见有系统性的研究报道,期待在此方向早日有所突破。

-

[1] Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, et al. Global cancer statistics 2018:GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries[J]. CA Cancer J Clin, 2018, 68(6):394-424. DOI: 10.3322/caac.21492

[2] 李德錄, 吴春晓, 郑莹, 等.上海市2003-2007年大肠癌发病率和死亡率分析[J].中国肿瘤, 2011, 20(06):413-418. http://d.old.wanfangdata.com.cn/Periodical/zgzl201106005 [3] Zhu J, Tan Z, Hollis-Hansen K, et al. Epidemiological trends in colorectal cancer in china:an ecological study[J]. Dig Dis Sci, 2017, 62(1):235-243. DOI: 10.1007/s10620-016-4362-4

[4] Chen W, Zheng R, Baade PD, et al. Cancer statistics in China, 2015[J]. CA Cancer J Clin, 2016, 66(2):115-132. DOI: 10.3322/caac.21338

[5] Feng RM, Zong YN, Cao SM, et al. Current cancer situation in China:good or bad news from the 2018 global cancer statistics[J]? Cancer Commun (Lond), 2019, 39(1):22. DOI: 10.1186/s40880-019-0368-6

[6] Siriwardena AK, Mason JM, Mullamitha S, et al. Management of colorectal cancer presenting with synchronous liver metastases[J]. Nat Rev Clin Oncol, 2014, 11(8):446-459. DOI: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2014.90

[7] Yin Z, Liu C, Chen Y, et al. Timing of hepatectomy in resectable synchronous colorectal liver metastases (SCRLM):simultaneous or delayed[J]? Hepatology, 2013, 57(6):2346-2357. DOI: 10.1002/hep.26283

[8] Nagarsheth N, Wicha MS, Zou W. Chemokines in the cancer microenvironment and their relevance in cancer immunotherapy[J]. Nat Rev Immunol, 2017, 17(9):559-572. DOI: 10.1038/nri.2017.49

[9] Zhao L, Lim SY, Gordon-Weeks AN, et al. Recruitment of a myeloid cell subset (CD11b/Gr1 mid) via CCL2/CCR2 promotes the development of colorectal cancer liver metastasis[J]. Hepatology, 2013, 57(2):829-839. http://www.wanfangdata.com.cn/details/detail.do?_type=perio&id=10.1002/hep.26094

[10] Lee AY, Phan TK, Hulett MD, et al. The relationship between CCR6 and its binding partners:does the CCR6-CCL20 axis have to be extended[J]? Cytokine, 2015, 72(1):97-101. http://www.wanfangdata.com.cn/details/detail.do?_type=perio&id=10.1177/1087057108322219

[11] Ghadjar P, Coupland SE, Na IK, et al. Chemokine receptor CCR6 expression level and liver metastases in colorectal cancer[J]. J Clin Oncol, 2006, 24(12):1910-1916. DOI: 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.1822

[12] Rubie C, Oliveira V, Kempf K, et al. Involvement of chemokine receptor CCR6 in colorectal cancer metastasis[J]. Tumour Biol, 2006, 27(3):166-174. http://www.wanfangdata.com.cn/details/detail.do?_type=perio&id=45288444764371279d9db6e1e1e03811

[13] Iwata T, Tanaka K, Inoue Y, et al. Macrophage inflammatory protein-3 alpha (MIP-3a) is a novel serum prognostic marker in patients with colorectal cancer[J]. J Surg Oncol, 2013, 107(2):160-166. DOI: 10.1002/jso.23247

[14] Cheng XS, Li YF, Tan J, et al. CCL20 and CXCL8 synergize to promote progression and poor survival outcome in patients with colorectal cancer by collaborative induction of the epithelial-mesenchymal transition[J]. Cancer Lett, 2014, 348(1-2):77-87. DOI: 10.1016/j.canlet.2014.03.008

[15] Li X, Zhong Q, Luo D, et al. The prognostic value of CXC subfamily ligands in stage Ⅰ-Ⅲ patients with colorectal cancer[J]. PLoS One, 2019, 14(4):e0214611. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0214611

[16] Halama N, Zoernig I, Berthel A, et al. Tumoral immune cell exploitation in colorectal cancer metastases can be targeted effectively by Anti-CCR5 therapy in cancer patients[J]. Cancer Cell, 2016, 29(4):587-601. DOI: 10.1016/j.ccell.2016.03.005

[17] Toiyama Y, Fujikawa H, Kawamura M, et al. Evaluation of CXCL10 as a novel serum marker for predicting liver metastasis and prognosis in colorectal cancer[J]. Int J Oncol, 2012, 40(2):560-566. http://www.wanfangdata.com.cn/details/detail.do?_type=perio&id=73304e79ba0aaa39d7519c565f4830b2

[18] Polaris Observatory Collaborators.Global prevalence, treatment, and prevention of hepatitis B virus infection in 2016:a modelling study[J]. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol, 2018, 3(6):383-403. DOI: 10.1016/S2468-1253(18)30056-6

[19] Huo T, Cao J, Tian Y, et al. Effect of concomitant positive hepatitis B surface antigen on the risk of liver metastasis:A retrospective clinical study of 4033 consecutive cases of newly diagnosed colorectal cancer[J]. Clin Infect Dis, 2018, 66(12):1948-1952. DOI: 10.1093/cid/cix1118

[20] Zhou F, Zhou J, Wang W, et al. Unexpected rapid increase in the burden of NAFLD in china from 2008 to 2018:A systematic review and meta-analysis[J]. Hepatology, 2019, 70(4):1119-1133. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31070259

[21] Estes C, Anstee QM, Arias-Loste MT, et al. Modeling NAFLD disease burden in China, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, Spain, United Kingdom, and United States for the period 2016-2030[J]. J Hepatol, 2018, 69(4):896-904. http://www.wanfangdata.com.cn/details/detail.do?_type=perio&id=f66fd69a15300b5f1f477426d409797f

[22] Jiang H, Room R, Hao W. Alcohol and related health issues in China:action needed[J]. Lancet Glob Health, 2015, 3(4):e190-191. DOI: 10.1016/S2214-109X(15)70017-3

[23] Li YM, Fan JG, et al. Guidelines of prevention and treatment for alcoholic liver disease (2018, China)[J]. J Dig Dis, 2019, 20(4):174-180. DOI: 10.1111/1751-2980.12687

[24] 延华, 鲁晓岚, 高艳琼, 等.西北地区脂肪性肝病的流行病学调查研究[J].中华肝脏病杂志, 2015, 23(8):622-627. DOI: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.1007-3418.2015.08.013 [25] Lian JQ, Yang XF, Zhao RR, et al. Expression profiles of circulating cytokines, chemokines and immune cells in patients with hepatitis B virus infection[J]. Hepat Mon, 2014, 14(6):e18892. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24976843

[26] Wu HL, Kao JH, Chen TC, et al. Serum cytokine/chemokine profiles in acute exacerbation of chronic hepatitis B:clinical and mechanistic implications[J]. J Gastroenterol Hepatol, 2014, 29(8):1629-1636. DOI: 10.1111/jgh.12606

[27] Zhou Y, Wang S, Ma JW, et al. Hepatitis B virus protein X-induced expression of the CXC chemokine IP-10 is mediated through activation of NF-kappaB and increases migration of leukocytes[J]. J Biol Chem, 2010, 285(16):12159-12168. DOI: 10.1074/jbc.M109.067629

[28] Haukeland JW, Damås JK, Konopski Z, et al. Systemic inflammation in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease is characterized by elevated levels of CCL2[J]. J Hepatol, 2006, 44(6):1167-1174. DOI: 10.1016/j.jhep.2006.02.011

[29] Chu X, Jin Q, Chen H, et al. CCL20 is up-regulated in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease fibrosis and is produced by hepatic stellate cells in response to fatty acid loading[J]. J Transl Med, 2018, 16(1):108. DOI: 10.1186/s12967-018-1490-y

[30] Hanson A, Piras IS, Wilhelmsen D, et al. Chemokine ligand 20(CCL20) expression increases with NAFLD stage and hepatic stellate cell activation and is regulated by miR-590-5p[J]. Cytokine, 2019, 123:154789. DOI: 10.1016/j.cyto.2019.154789

[31] Zhang X, Shen J, Man K, et al. CXCL10 plays a key role as an inflammatory mediator and a non-invasive biomarker of non-alcoholic steatohepatitis[J]. J Hepatol, 2014, 61(6):1365-1375. DOI: 10.1016/j.jhep.2014.07.006

[32] Fisher NC, Neil DA, Williams A, et al. Serum concentrations and peripheral secretion of the beta chemokines monocyte chemoattractant protein 1 and macrophage inflammatory protein 1alpha in alcoholic liver disease[J]. Gut, 1999, 45(3):416-420. DOI: 10.1136/gut.45.3.416

[33] Degré D, Lemmers A, Gustot T, et al. Hepatic expression of CCL2 in alcoholic liver disease is associated with disease severity and neutrophil infiltrates[J]. Clin Exp Immunol, 2012, 169(3):302-310. DOI: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2012.04609.x

[34] Qiu HB, Zhang LY, Zeng ZL, et al. HBV infection decreases risk of liver metastasis in patients with colorectal cancer:A cohort study[J]. World J Gstroenterol, 2011, 17(6):804-808. DOI: 10.3748/wjg.v17.i6.804

[35] Wei XL, Qiu MZ, Chen WW, et al. The status of HBV infection influences metastatic pattern and survival in Chinese patients with pancreatic cancer[J]. J Transl Med, 2013, 11(8):249. http://d.old.wanfangdata.com.cn/OAPaper/oai_pubmedcentral.nih.gov_3851713

[36] Earl TM, Nicoud IB, Pierce JM, et al. Silencing of TLR4 decreases liver tumor burden in a murine model of colorectal metastasis and hepatic steatosis[J]. Ann Surg Oncol, 2009, 16(4):1043-1050. DOI: 10.1245/s10434-009-0325-8

[37] Ohashi K, Wang Z, Yang YM, et al. NOD-like receptor C4 inflammasome regulates the growth of colon cancer liver metastasis in NAFLD[J]. Hepatology, 2019, 70(5):1582-1599. DOI: 10.1002/hep.30693

[38] Hamady ZZ, Rees M, Welsh FK, et al. Fatty liver disease as a predictor of local recurrence following resection of colorectal liver metastases[J]. Br J Surg, 2013, 100(6):820-826. DOI: 10.1002/bjs.9057

[39] Mohr AM, Gould JJ, Kubik JL, et al. Enhanced colorectal cancer metastases in the alcohol-injured liver[J]. Clin Exp Metastasis, 2017, 34(2):171-184. DOI: 10.1007/s10585-017-9838-x

[40] Im HJ, Kim HG, Lee JS, et al. A Preclinical model of chronic alcohol consumption reveals increased metastatic seeding of colon cancer cells in the liver[J]. Cancer Res, 2016, 76(7):1698-1704. DOI: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-15-2114

[41] Maeda M, Nagawa H, Maeda T, et al. Alcohol consumption enhances liver metastasis in colorectal carcinoma patients[J]. Cancer, 1998, 83(8):1483-1488. DOI: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0142(19981015)83:8<1483::AID-CNCR2>3.0.CO;2-Z

下载:

下载: