Differences in brain cortical structure between non-small cell lung cancer patients and healthy controls: a retrospective magnetic resonance imaging study

-

摘要:目的 分析非小细胞肺癌(non-small cell lung cancer,NSCLC)患者颅脑核磁共振影像学(magnetic resonance imaging,MRI)改变,并探讨其相关的影响因素,为患者的脑健康预防及保护提供依据。方法 选取2018年7月至2019年3月四川省肿瘤医院45例初诊为NSCLC(癌症组)及39例健康对照组(正常组)颅脑MRI数据,利用Freesurfer软件对MRI数据进行基于大脑皮层表面形态学测量(surface-based morphometry,SBM)分析,统计对比癌症组与正常组的脑区变化,利用偏相关分析方法将血常规、血脂、肿瘤标志物与变化脑区行相关性分析。结果 与正常组相比,癌症组右脑中央后回及顶叶上回脑皮质体积明显萎缩(P < 0.05),但其厚度、表面积、曲率、脑沟深度未见明显变化(P>0.05)。此外,癌症组神经元特异性烯醇化酶(neuron-specific enolase,NSE)水平明显高于正常组[(27.02±33.16)ng/mL vs.(7.8±3.85)ng/mL,P < 0.05],相关性分析结果显示中央后回体积萎缩与NSE呈负相关(r=-0.268,P=0.039),血常规、血脂、癌胚抗原(carcinoembryonic antigen,CEA)与中央后回体积萎缩无明显相关性。结论 NSCLC可导致右脑中央后回及顶叶上回体积缩小,且中央后回体积缩小与NSE呈显著负相关,提示NSE可作为预测NSCLC相关脑损伤的潜在预测分子。

-

关键词:

- 肺癌 /

- 非小细胞肺癌 /

- 大脑皮层 /

- 癌症相关认知功能障碍

Abstract:Objective To analyze changes on brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) in patients with non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) and to determine the influencing factors to provide evidence for the prevention and maintenance of brain health in patients with cancer.Methods Forty-five newly diagnosed patients with NSCLC (cancer group) and 39 healthy controls (control group) were enrolled at Sichuan Cancer Hospital & Institute from July 2018 to March 2019. MRI data were analyzed based on surface-based morphometry (SBM) of the cerebral cortex. Changes in brain regions were statistically compared between the two groups. Routine blood markers, blood lipid profiles, tumor markers, and changes in brain regions were analyzed using partial correlation analysis.Results Regarding changes in cerebral cortex volume, the right posterior central gyrus and right superior parietal gyrus were significantly atrophied in the cancer group compared to that in the control group (P < 0.05); however, the thickness, surface area, curvature, and sulcus depth were not significantly different (P>0.05). In addition, the level of neuron-specific enolase (NSE) in the cancer group was significantly higher than that in the control group [(27.02± 33.16) ng/mL vs. (7.8±3.85) ng/mL, P < 0.05]. Partial correlation analysis showed that the atrophy volume of the central posterior gyrus was negatively correlated with NSE levels (r=-0.268, P=0.039); However, the atrophy volume of the central posterior gyrus was not significantly correlated with routine blood markers, blood lipid profiles, and carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) levels.Conclusions Volumes of the posterior central gyrus and superior parietal gyrus of the right brain are atrophied in NSCLC patients, and volume reduction in the posterior central gyrus is significantly negatively correlated with NSE levels. These findings suggest that NSE can be used as a potential predictor of NSCLCrelated brain damage. -

1983年,Silberfarb[1]首次提出癌症相关性认知功能损害(cancer-related cognitive impairment,CRCI),是指癌症导致患者脑部功能结构受损而出现认知功能障碍。1990年后,大量临床研究相继表明化疗[2-3]、放疗[4]、激素治疗[5-6]会导致患者认知功能的损伤[7]。2000年,肿瘤本身也被证实可影响认知功能和大脑结构[8-10]。目前为止,大部分神经解剖学结果都来自于对乳腺癌患者的核磁共振(MRI)研究,对肺癌患者大脑皮层结构变化的影像学研究较少,且研究结果差异较大。肺癌在全球发病率及死亡率排行中稳居首位,分别占癌症总发病人群的11.6%和18.4%[11],非小细胞肺癌(non-small lung cancer,NSCLC)占肺癌的85%,是癌症相关死亡的主要原因[12],NSCLC的高发病率及死亡率迫使研究者们进一步研究NSCLC患者脑结构变化。本研究旨在探索初诊NSCLC患者的大脑皮层变化及临床相关影响因素,为肺癌患者脑健康保护提供依据。

1. 材料与方法

1.1 研究对象

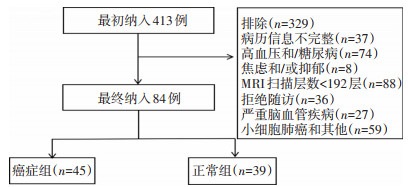

收集2018年7月至2019年3月就诊于四川省肿瘤医院的初诊NSCLC患者(癌症组)337例,最终符合纳入标准的癌症组45例(图 1),收集癌症组颅脑MRI和血液分析(包括白细胞数、血红蛋白浓度、血小板数)、血脂指标(胆固醇、甘油三脂)、肿瘤标志物[癌胚抗原(carcinoembryonic antigen,CEA)、神经元特异性烯醇化酶(neuron-specific endase,NSE)]等临床参数。同时收集76例四川省肿瘤医院肿瘤筛查中心健康成年人为正常组,最终纳入39例(图 1),整理收集基本信息,包括性别、年龄、生活习惯(烟酒史)、血液分析、血脂指标、肿瘤标志物、基础疾病(高血压、糖尿病、心血管疾病、精神疾病病史)。

癌症组纳入标准:1)病理活检证实为NSCLC(鳞癌/ 腺癌),不合并其他恶性肿瘤;2)影像学检查提示无严重脑血管疾病、无脑转移征象;3)无神经系统或精神疾病病史;4)核磁扫描层数为192层;5)使用3.0T SIEMENSAvanto核磁共振机进行的薄层扫描;6)右利手。

正常组入组标准:1)四川省肿瘤医院肿瘤筛查中心检查提示无恶性肿瘤;2)既往无恶性肿瘤病史;3)无神经系统或精神疾病病史;4)核磁扫描层数为192层;5)使用3.0T SIEMENS-Avanto核磁共振机进行的薄层扫描;6)右利手。

排除标准:1)有神经系统或精神疾病病史;2)有颅内转移、颅内浸润、原发脑肿瘤、抑郁、焦虑及严重脑血管病变;3)高血压、糖尿病病史[13-15];4)非四川省肿瘤医院核磁共振室3.0T SIEMENS-Avanto核磁共振机扫描结果;5)核磁扫描层数<192层;6)左利手。

肺癌分期按美国癌症联合委员会(AJCC)分期系统第8版进行分期。本研究通过四川省肿瘤医院伦理审查委员会批准。

1.2 研究方法

所有颅脑MRI影像学数据均为四川省肿瘤医院3.0T SIEMENS-Avanto核磁共振机进行的薄层扫描,采取结构像3D加权MRI图像:参数设置为重复时间(repetition time,TR)=1 160 ms,回波时间(echo time,TE)=4.24 ms,反转时间(inversion time,TI)=600 ms,视野(field of view,FOV)=256×256 mm2,翻转角度(flip angle,FA)=15°,data matrix=256×256,voxel size=1.0×1.0×1.0 mm3,脑区由192层横断平面组成。获取MRI影像后,使用Freesurfer软件(版本6.0)进行皮层表面重建和形态学参数测量。具体步骤如下:1)将个体的T1加权图像配准到Talairach标准空间上;2)在标准空间中标准化图像的灰度值,提高图像对比度,减少分割误差;3)去除颅骨等非脑组织;4)根据图像的对比度等多个信息,标定大脑的白质区域,并且可以根据标准空间中脑桥和胼胝体的位置,去除小脑以及脑干并将大脑分成左右两个半球;5)分别将左右半球进行曲面的三角网格参数化。用两个三角形代表灰质和白质交界面的体素,可以得到灰质和白质交界面的初步三角网格曲面,但是体素水平上仍需要进行平滑处理。对软膜曲面(从灰质和白质交界面向外扩展到灰质与脑脊液的交界面)进行变形,至此得到软膜曲面和白质曲面用顶点来表述;6)计算每个顶点的皮层厚度等参数;7)使用Destrieux Atlas模板划分脑区,计算每个脑区的皮层厚度、体积、表面积、曲率、脑沟深等指标。

1.3 统计学分析

采用SPSS 24.0软件进行统计学分析。利用Freesurfer中的QDEC(query,design,estimate,contrast)交互统计,对脑区的厚度、体积、表面积、曲率、脑沟深度进行组间对比。组间差异通过在P < 0.05(两尾)处的蒙特卡洛检验进行校正。年龄使用独立样本t检验分析。性别、吸烟、饮酒采用χ2检验分析,临床参数(血液分析、血脂指标、肿瘤标志物)采用χ2检验或Fisher精确检验。双样本t检验分析正常组与癌症组的大脑皮层变化脑区。以P < 0.05为差异具有统计学意义。

2. 结果

2.1 癌症组和正常组基本信息

正常组39例,男性20例、女性19例,平均年龄(48.9± 12.5)岁,年龄范围为21~81岁;癌症组共45例肺癌患者,男性28例、女性17例,平均年龄为(57.0±8.2)岁,年龄范围为36~70岁。临床分期:Ⅰ期3例,Ⅱ期7例,Ⅲ期20例,Ⅳ期15例;病理类型:鳞癌28例,腺癌17例;两组年龄、吸烟状况差异具有统计学意义,性别、饮酒差异无统计学意义(表 1)。

表 1 癌症组与正常组的临床资料

2.2 脑区皮层平均厚度、体积、表面积、曲率、脑沟深度变化

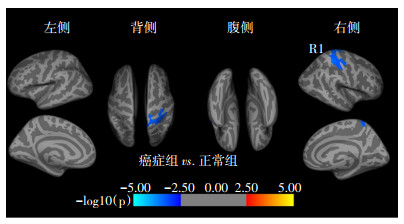

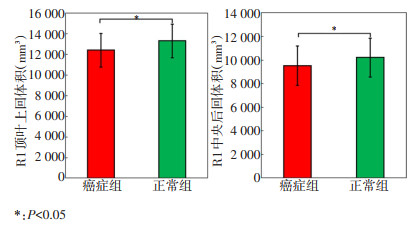

临床资料统计结果显示,癌症组与正常组年龄及吸烟差异具有统计学意义,所以在对比两组脑区结构变化时将年龄、吸烟作为协变量,规避其对数据结果的影响,最终结果显示右侧大脑半球顶叶皮层体积缩小,主要表现在中央后回及顶叶上回部位脑皮质体积萎缩(图 2,表 2),癌症组与正常组大脑皮层体积差异变化见图 3。癌症组脑区皮层厚度、表面积、曲率、脑沟深度与正常组对比无显著性差异。

表 2 正常组与癌症组皮层体积变化脑区

2.3 病理类型、临床分期对脑区的影响

癌症组共纳入鳞癌28例,腺癌17例。按AJCC第8版分期,分为Ⅰ期3例,Ⅱ期7例,Ⅲ期20例,Ⅳ期15例。通过QDEC双样本t检验分析,结果显示,病理类型、临床分期对本研究变化脑区无影响。

2.4 癌症组血液分析、血脂等临床参数与体积缩小脑区相关性分析结果

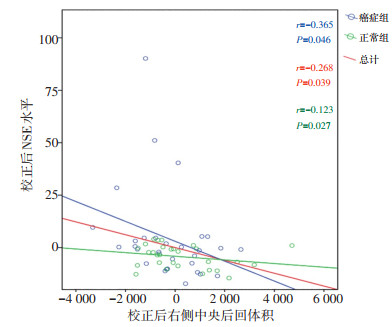

以性别、年龄、吸烟、饮酒作为控制变量计算偏相关系数,分析癌症组临床参数与体积减少脑区的相关性。癌症组与正常组对比结果显示,体积缩小脑区与临床参数(血液分析、血脂、CEA)未见明显相关性;右侧大脑体积减小的中央后回与NSE呈负相关(图 4)。

3. 讨论

本研究旨在利用解剖学、皮层结构等信息,为建立肺癌患者大脑皮层变化模型提供影像学依据。本研究发现NSCLC患者在接受临床治疗前右侧大脑皮层中央后回及顶叶上回出现体积萎缩,厚度、表面积、曲率及脑沟深度等指标无显著性变化。癌症导致大脑皮质体积萎缩的结果与目前的相关研究结果一致[16-17]。将体积缩小脑区与临床参数做相关性分析,结果显示右侧大脑中央后回体积减小与NSE呈负相关。

年龄对大脑结构的影响最开始表现在额叶皮层,其次才是颞叶[18-19]和顶叶皮层[20],前脑区域(例如前额叶皮层)是第一个与年龄相关的缺陷区域[21],本研究结果显示仅顶叶上回及中央后回体积缩小,额叶和颞叶体积却无显著性差异,说明本研究两组受试者的年龄差异对大脑结构变化的影响不大。此外,吸烟所致的大脑衰老多为全脑及海马萎缩[22],而本研究结果显示变化脑区集中在右脑,且为部分脑区而非全脑,因此结果中顶叶体积的缩小并未受吸烟的影响。为避免年龄及吸烟影响本研究结果,在计算脑区皮层变化时,将性别、年龄、吸烟、饮酒作为协变量,避免了上述因素对数据结果的影响。因此,虽然癌症组与正常组年龄及吸烟存在差异,但本研究脑区变化的结果不受年龄及吸烟的影响,数据结果可靠。

本研究结果提示,大脑皮层变化集中在顶叶,这与肺癌患者在接受治疗前的右侧顶叶会出现低代谢区[23]、白质普遍减少[24]等研究结果一致。顶叶的功能包括躯体感觉、语言、计算、自我运动知觉和视觉空间意识[25],右顶叶受损可导致空间关系障碍,如书写过程中对词距、行距的把握等。而中央后回是躯体感觉区,整合各种体感刺激,实现对物体的形状、质地和重量正确的辨认。因此,顶叶上回及中央后回体积的缩小提示肺癌患者在初诊时不仅会出现大脑皮质体积的缩小,临床表现上也可能已经出现推理、感知、空间感受等认知功能障碍。有研究报道,肺癌患者在化疗前即表现出认知障碍,在接受治疗之前存在言语记忆缺陷以及广泛的白质损伤[24],证实大脑皮质的损害与认知功能存在相关性。目前CRCI的病理生理机制已有相关研究,如肿瘤相关巨噬细胞释放促炎细胞因子改变了肿瘤周围微环境[26],大脑中较高水平的促炎细胞因子对神经具有毒性,可诱发人类神经退行性疾病[27];非中枢神经系统癌细胞释放的外泌体可在局部发挥作用,调节细胞机制,直接影响脑活动和认知功能,同时能够激活癌细胞脑转移,损害血脑屏障的完整性;此外,外泌体还可通过免疫细胞的外周免疫攻击触发大脑的应激反应[28],外泌体含量及其释放的变化可引起大脑解剖结构的改变[29]。癌症所致大脑结构变化的具体机制复杂且精细,至今尚无明确的解释,CRCI具体机制仍是当前脑科学的研究重点,要求更多的前瞻性、多中心、综合性、大数据研究对CRCI进行进一步探讨。

NSE是烯醇化酶的二聚体同位酶,主要存在于成熟神经元和神经元起源细胞中[30-31],在小细胞肺癌中发现NSE值增加[32],同时大量研究已证实NSE与小细胞肺癌的生存率、疾病分期、远处转移、肿瘤进展等显著相关[33-35],而NSE与NSCLC的相关性研究较少,因此本研究初聚焦于NSCLC患者。近年来,NSCLC相关研究表明NSE不仅是诊断NSCLC的潜在生物标志物[36],更是肺癌骨转移、脑转移的危险因素及预测因子[37-38],被认为是NSCLC的潜在预后指标[39],但未见NSE与特定脑区结构变化的相关性研究。本研究对体积缩小脑区与临床参数进行相关性分析,结果显示NSE与右侧大脑中央后回体积减小呈负相关,其可能原因是NSE是神经元损伤的生物标志物[40],神经元和神经组织的减少最终导致脑区体积缩小。当癌细胞穿透血脑屏障,损伤神经组织,导致NSE释放到脑脊液中,进入血液[32],最终使外周血NSE浓度增高。但本研究结果中NSE与中央后回这一特定脑区体积缩小呈负相关的具体原因及机制有待进一步研究探索。

本研究存在的不足为回顾性研究,选择偏差是不可避免的,本研究结果需要前瞻性队列研究来进行验证。此外,本研究中的Freesurfer图像处理方法主要依赖于大脑皮层表面形态学测量(surface-based morphometry,SBM),可能与大多数其他结构MRI研究的CRCI结果不同。最后,本研究缺乏认知功能评估量表,不能将特定脑区变化与特定认知功能变化进行相关性分析。为克服以上缺点,后续研究中将设置肺癌患者自身前后对照组,采集肺癌患者治疗前、治疗中、治疗后颅脑MRI及认知功能评价,将神经影像学分析与临床神经心理学测试相结合,进一步分析大脑结构与认知功能相关性。

综上所述,本研究显示未接受任何治疗前的NSCLC患者右侧大脑中央后回及顶叶上回体积缩小,进一步证实了癌症本身对大脑结构的影响,同时发现NSE与中央后回体积缩小呈负相关,为大脑损伤提供了新的标志物。

-

表 1 癌症组与正常组的临床资料

表 2 正常组与癌症组皮层体积变化脑区

-

[1] Oxman TE, Silberfarb PM. Serial cognitive testing in cancer patients receiving chemotherapy[J]. Am J Psychiatry, 1980, 137(10): 1263-1265. DOI: 10.1176/ajp.137.10.1263

[2] Ahles TA, Saykin AJ. Candidate mechanisms for chemotherapy-induced cognitive changes[J]. Nat Rev Cancer, 2007, 7(3): 192-201. DOI: 10.1038/nrc2073

[3] Simó M, Rifà- Ros X, Rodriguez- Fornells A, et al. Chemobrain: A systematic review of structural and functional neuroimaging studies[J]. Neurosci Biobehav Rev, 2013, 37(8): 1311-1321. DOI: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2013.04.015

[4] Asher A, Myers JS. The effect of cancer treatment on cognitive function [J]. Clin Adv Hematol Oncol, 2015, 13(7): 441-450. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26353040

[5] Chao HH, Hu S, Ide JS, et al. Effects of androgen deprivation on cerebral morphometry in prostate cancer patients-an exploratory study[J]. PLoS One, 2013, 8(8): e72032. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0072032

[6] Zec RF, Trivedi MA. The effects of estrogen replacement therapy on neuropsychological functioning in postmenopausal women with and without dementia: a critical and theoretical review[J]. Neuropsychol Rev, 2002, 12(2): 65-109. DOI: 10.1023/A:1016880127635

[7] Horowitz TS, Suls J, Treviño M. A call for a neuroscience approach to cancer-related cognitive impairment[J]. Trends Neurosci, 2018, 41(8): 1-3. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/29907436

[8] Liu S, Li X, Ma R, et al. Cancer-associated changes of emotional brain network in non-nervous system metastatic non-small cell lung cancer patients: a structural connectomic diffusion tensor imaging study[J]. Transl Lung Cancer Res, 2020, 9(4): 1101-1111. DOI: 10.21037/tlcr-20-273

[9] Kesler SR, Adams M, Packer M, et al. Disrupted brain network functional dynamics and hyper- correlation of structural and functional connectome topology in patients with breast cancer prior to treatment [J]. Brain Behav, 2017, 7(3): e00643. DOI: 10.1002/brb3.643

[10] Menning S, de Ruiter MB, Veltman DJ, et al. Multimodal MRI and cognitive function in patients with breast cancer prior to adjuvant treatment—the role of fatigue[J]. NeuroImage Clin, 2015, 7: 547-554. DOI: 10.1016/j.nicl.2015.02.005

[11] Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, et al. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries[J]. CA Cancer J Clin, 2018, 68(6): 394-424. DOI: 10.3322/caac.21492

[12] Kauffmann-Guerrero D, Kahnert K, Huber RM. Treatment sequencing for anaplastic lymphoma kinase-rearranged non-small-cell lung cancer [J]. Drugs, 2021, 81(1): 87-100. DOI: 10.1007/s40265-020-01445-2

[13] Groeneveld O, Reijmer Y, Heinen R, et al. Brain imaging correlates of mild cognitive impairment and early dementia in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus[J]. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis, 2018, 28(12): 1-8. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30355471

[14] Rom S, Zuluaga-Ramirez V, Gajghate S. Hyperglycemia-driven neuroinflammation compromises BBB leading to memory loss in both diabetes mellitus (DM) type 1 and type 2 mouse models[J]. Mol Neurobiol, 2019, 56(3): 1883-1896. DOI: 10.1007/s12035-018-1195-5

[15] Mossello E, Simoni D. High blood pressure in older subjects with cognitive impairment[J]. Monaldi Arch Chest Dis, 2016, 84(1-2): 32-36. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27374044

[16] Amidi A, Wu LM. Structural brain alterations following adult non-CNS cancers: a systematic review of the neuroimaging literature[J]. Acta Oncol, 2019, 58(5): 522-536. DOI: 10.1080/0284186X.2018.1563716

[17] Madhyastha S, Somayaji SN, Rao MS, et al. Hippocampal brain amines in methotrexate- induced learning and memory deficit[J]. Can J Physiol Pharmacol, 2002, 80(11): 1076-1084. DOI: 10.1139/y02-135

[18] Bartzokis G, Beckson M, Lu PH, et al. Age-related changes in frontal and temporal lobe volumes in men: a magnetic resonance imaging study [J]. Arch Gen Psychiatry, 2001, 58(5): 461- 465. DOI: 10.1001/archpsyc.58.5.461

[19] Raz N, Lindenberger U, Rodrigue KM, et al. Regional brain changes in aging healthy adults: general trends, individual differences and modifiers[J]. Cereb Cortex, 2005, 15(11): 1676-1689. DOI: 10.1093/cercor/bhi044

[20] Resnick SM, Pham DL, Kraut MA, et al. Longitudinal magnetic resonance imaging studies of older adults: a shrinking brain[J]. J Neurosci, 2003, 23(8): 3295-3301. DOI: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-08-03295.2003

[21] Sowell ER, Thompson PM, Toga AW. Mapping changes in the human cortex throughout the span of life[J]. Neuroscientist, 2004, 10(4): 372- 392. DOI: 10.1177/1073858404263960

[22] Debette S, Seshadri S, Beiser A, et al. Midlife vascular risk factor exposure accelerates structural brain aging and cognitive decline[J]. Neurology, 2011, 77(5): 461-468. DOI: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e318227b227

[23] Li WL, Fu C, Xuan A, et al. Preliminary study of brain glucose metabolism changes in patients with lung cancer of different histological types[J]. Chin Med J (Engl), 2015, 128(3): 301-304. DOI: 10.4103/0366-6999.150089

[24] Simo M, Root JC, Vaquero L, et al. Cognitive and brain structure changes in a lung cancer population[J]. J Thorac Oncol, 2015, 10(1): 38-45. DOI: 10.1097/JTO.0000000000000345

[25] Velásquez C, Goméz E, Martino J. Mapping visuospatial and self-motion perception functions in the left parietal lobe[J]. Neurosurg Focus, 2018, 45(Suppl2): V8. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30269556

[26] Allavena P, Mantovani A. Immunology in the clinic review series; focus on cancer: Tumour associated macrophages: undisputed stars of the inflammatory tumour microenvironment[J]. Clin Exp Immunol, 2012, 167(2): 195-205. DOI: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2011.04515.x

[27] Zipp F, Aktas O. The brain as a target of inflammation: common pathways link inflammatory and neurodegenerative diseases[J]. Trends Neurosci, 2006, 29(9): 518-527. DOI: 10.1016/j.tins.2006.07.006

[28] Koh YQ, Tan CJ, Toh YL, et al. Role of exosomes in cancer-related cognitive impairment[J]. Int J Mol Sci, 2020, 21(8): 2755-2770. DOI: 10.3390/ijms21082755

[29] Hinzman CP, Baulch JE, Mehta KY, et al. Plasma-derived extracellular vesicles yield predictive markers of cranial irradiation exposure in mice [J]. Sci Rep, 2019, 9(1): 9460-9468. DOI: 10.1038/s41598-019-45970-x

[30] Schmechel D, Marango P, Brightman M. Neurone-specific enolase is a molecular marker for peripheral and central neuroendocrine cells[J]. Nature, 1978, 276(5690): 834-836. DOI: 10.1038/276834a0

[31] Tapia FJ, Polak J, Barbosa AJ, et al. Neuron-specific enolase is produced by neuroendocrine tumours[J]. Lancet, 1981, 1(8224): 808-811. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/6111674

[32] Lamers KJ, Vos P, Verbeek MM, et al. Protein S-100B, neuron-specific enolase (NSE), myelin basic protein (MBP) and glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and blood of neurological patients[J]. Brain Res Bull, 2003, 61(3): 261-264. DOI: 10.1016/S0361-9230(03)00089-3

[33] Huang Z, Xu D, Zhang F, et al. Pro-gastrin-releasing peptide and neuronspecific enolase: useful predictors of response to chemotherapy and survival in patients with small cell lung cancer[J]. Clin Transl Oncol, 2016, 18(10): 1019-1025. DOI: 10.1007/s12094-015-1479-4

[34] Zhou M, Wang Z, Yao Y, et al. Neuron-specific enolase and response to initial therapy are important prognostic factors in patients with small cell lung cancer[J]. Clin Transl Oncol, 2017, 19(7): 865-873. DOI: 10.1007/s12094-017-1617-2

[35] Liu X, Zhang W, Yin W, et al. The prognostic value of the serum neuron specific enolase and lactate dehydrogenase in small cell lung cancer patients receiving first-line platinum-based chemotherapy[J]. Medicine (Baltimore), 2017, 96(46): e8258. DOI: 10.1097/MD.0000000000008258

[36] Dong Y, Zheng X, Yang Z, et al. Serum carcinoembryonic antigen, neuronspecific enolase as biomarkers for diagnosis of non-small cell lung cancer[J]. J Cancer Res Ther, 2016, 12(Suppl): 34-36. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27721249

[37] Zhou Y, Chen WZ, Peng A, et al. Neuron-specific enolase, histopathological types, and age as risk factors for bone metastases in lung cancer[J]. Tumour Biol, 2017, 39(7): 1-5. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28671048

[38] 陈燕, 彭伟, 黄艳芳, 等. 治疗前血清神经元特异性烯醇化酶水平在预测晚期非小细胞肺癌脑转移及预后中的意义[J]. 中华肿瘤杂志, 2015, 37(7): 508-511. DOI: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.0253-3766.2015.07.006 [39] Tiseo M, Ardizzoni A, Cafferata MA, et al. Predictive and prognostic significance of neuron- specific enolase (NSE) in non-small cell lung cancer[J]. Anticancer Res, 2008, 28(1B): 507-513. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18383893

[40] Ganti L, Serrano E, Toklu HZ. Can neuron specific enolase be a diagnostic biomarker for neuronal injury in COVID-19[J]? Cureus, 2020, 12 (10): e11033. http://www.researchgate.net/publication/346279323_Can_Neuron_Specific_Enolase_Be_a_Diagnostic_Biomarker_for_Neuronal_Injury_in_COVID-19

-

期刊类型引用(1)

1. 王尚虎,闵旭红,宋彪,宋奇隆,王杰,曾嵘,盛蕾. 非小细胞肺癌患者认知功能和生命质量的影响因素分析. 临床肺科杂志. 2023(06): 843-847 .  百度学术

百度学术

其他类型引用(2)

下载:

下载: